Designing The Golden Butterfly

As many people have already noticed, the cover design for The Golden Butterfly is spectacular. It’s the wonderful work of Stripes designer Pip Johnson. She’s been kind enough to spend some time answering a few questions about how she went about designing this cover, and about the art of book cover design in general.

What’s your starting point when you begin to think about designing a cover? Was it any different when you began to think about The Golden Butterfly?

I always read the manuscript before starting any design work, as I find the atmosphere I pick up on usually sets the tone for how the cover will look when it is finished, and I try not to lose that feeling the book first gave me, through all the multiple drafts and re-workings! I want the potential reader to get an immediate sense of how the book will make them feel. Getting that hunch across is particularly important for a book of this type - for example with younger fiction the focus tends to be on having the characters on the cover, interacting in a some way, but for MG and older fiction to YA the possibilities are endless and I think atmosphere is all - from the palette, choice of image, rendering and typography - to me this leads to a really good book cover.

When you got the brief for The Golden Butterfly, what were your initial thoughts about what you ideally wanted to see on the cover?

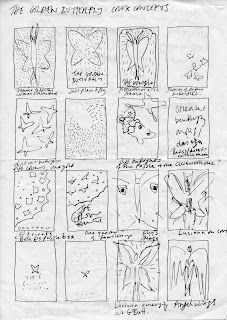

Having a cover brief is so important for focussing your ideas, editorial and sometimes marketing too, will give the designer some pointers, for example who the reader is (what kinds of books they already love to read), the approximate age range it is for, and how they imagine it, as I mentioned before the possibilities are endless so it's great if the editor and designer are 'on the same page' from the outset. For The Golden Butterfly I was asked to come up with something ‘sumptuous, escapist and visually beautiful, a desirable object for someone who covets books…Fans of Katherine Woodfine, Robin Stevens, Katherine Rundell, and Jennifer Bell’. I doodled a few ideas in the margins as I read it, one thing that kept popping to mind was the feeling of a nighttime adventure - running through city streets to find answers to the puzzle and how exciting this was and wanting to get that feeling on the cover, but the central image was very clear to me right at the start of the process, a victorious female figure rising up with a shower of light spreading out to the edges. The final design is very similar to the first thumbnail concept I drew, which is pretty rare!

Can you outline the process that you go through as a designer when you’re working on a book cover?

It is a long process... but great fun.

Read the manuscript, discuss the brief with the editor, quickly draw multiple thumbnail sketches - I find if I do this without thinking too hard, cover concepts tend to pop up in my head as I go along. I choose the best ideas and talk to my art director about which ones to take to the design meeting with the editor and editorial director. At this meeting we decide which of those drafts or scamps as they are sometimes called, to work up even further, and we look at any illustrators and shortlist the ones we would like to work on the final design, to show to our sales and marketing department - their input is invaluable as although we keep up with current trends, our sales and marketing people know what is out there and what is working in terms of cover design as they get direct feedback from buyers (who buy books for their various book shops and chain stores such as Waterstones and WHS, and supermarkets for example). Sometimes we don't commission an illustrator as we illustrate the cover, or create the images for the cover ourselves, as with The Golden Butterfly. Once a cover direction and illustrator has been agreed on, we present the ideas to the author and their agent. Any feedback and concerns from the author and agent are taken in and a final design is mocked up before briefing the illustrator to work on the final design. Quite often the illustrator works on the design at a much earlier point, and their ideas are worked into the design from the start too, usually though we try to have the final design of the cover decided upon before we ask the illustrator to start working their magic!

For you, what’s the most important element to consider when you’re designing a middle grade book cover?

Immediate impact - getting a sense of the story across visually, sparking curiosity in the viewer. There's a lot of competition out there, so many incredible stories wrapped up in beautiful jackets! I spend quite a lot of my free time wondering around bookshops and getting a bit dizzy looking at all the stunning books out there on table tops and in windows, if I could sum up my mood when doing this it would be the dribble face emoji followed by the crazy face emoji.

Can you talk a little about how you chose the colours for The Golden Butterfly? I remember that it changed throughout the process – why was that?

The first draft was a deep maroon red, with gold, this was when we thought of setting the character rising up in the theatre itself, the figures in the front row of the theatre picked out by the light bouncing off the tops and brims of their top hats, and light picking out the proscenium arch too, but I think we decided this felt too enclosed so we took away the arch, then decided that we wanted it to feel more epic so went for a cityscape instead. As it was now set outside we chose the deep navy and rich blues to complement the gold foil.

What other changes were made as the cover was developed? How different was the final design to your initial suggestions, for example?

It was taken from the indoor theatre setting, to outdoor cityscape, and the original drawing of the figure had arms, but this interrupted the line of the butterfly wings so we decided not to have them showing. I also drew several versions of the figure with the dashes of light, it took a few goes to get the silhouette looking right, first I drew out the main image in pencil, then used a light box to draw the sparks in fine liner pen. Otherwise compared with other covers I've worked on the final design was pretty much a combination of those initial ideas!

Does there come a point when you’re designing that you look at what’s on your screen and think ‘Yes! That’s it!’?

Multiple times, but then you come back a few days later and look at it with fresh eyes and see what needs changing! Also it's really important to be flexible as what we might think is 'it' isn't the same as what the author, or sales and marketing thinks for example. This leads to working a bit harder, pushing ideas further, and almost always results in a better cover. We also depend very much on our art director, who will spot things we haven't, and literally direct the cover to a better place! It's especially hard to be objective if you are illustrating the cover yourself, as you focus in so much on the drawing and it's difficult to step back and see the cover as a whole, so for this one I needed a lot more direction than usual.

How does it work when you’re using foil in the process? Do you get a proof from the printer so that you can see how it looks, or is it a case of waiting until the advance copies arrive?

Once the illustration is in Photoshop, we take all the elements that are to to be foiled and put a 'gradient' effect over them - this is how we do the effect on covers that are just digital, so viewed on screen or printed in catalogues or on posters, if you do it carefully it looks just like real foil. We only get to see the final result when the advance copies come in, but if there are any potential issues with it, our printer will always let us know before they create the special metal plate (called a foiling die), which prints the foil on top of the cover. I recently went on a trip to our printer, CPI, and got to see how all this is done, it is amazing!

How happy are you with the way The Golden Butterfly cover turned out?

I know it's a good cover and there have been lots of lovely comments - I think it does its job really well in that the atmosphere of the story - nighttime, adventure, a bit of magic, a euphoric moment, are all there. It’s also an incredibly good feeling when you know you’ve made the author happy! I loved reading it and re-reading it - just my cup of tea, so glad I put my hand in the air and asked to work on it when I first heard about it!

Thank you so much, Pip - both for the beautiful cover, which I adore (and I know many others do too) and for taking the time to talk about your process. Can’t wait to see your next fabulous cover!